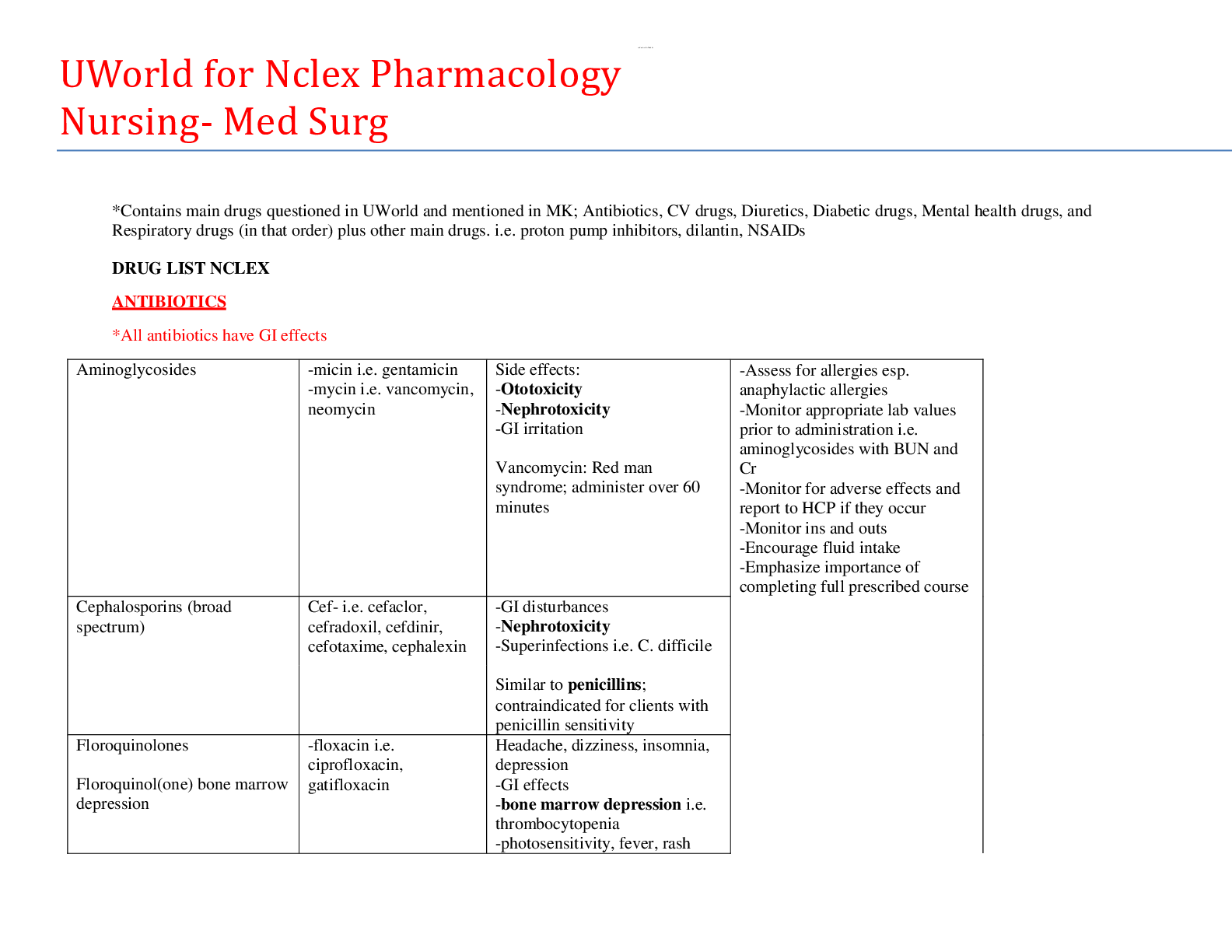

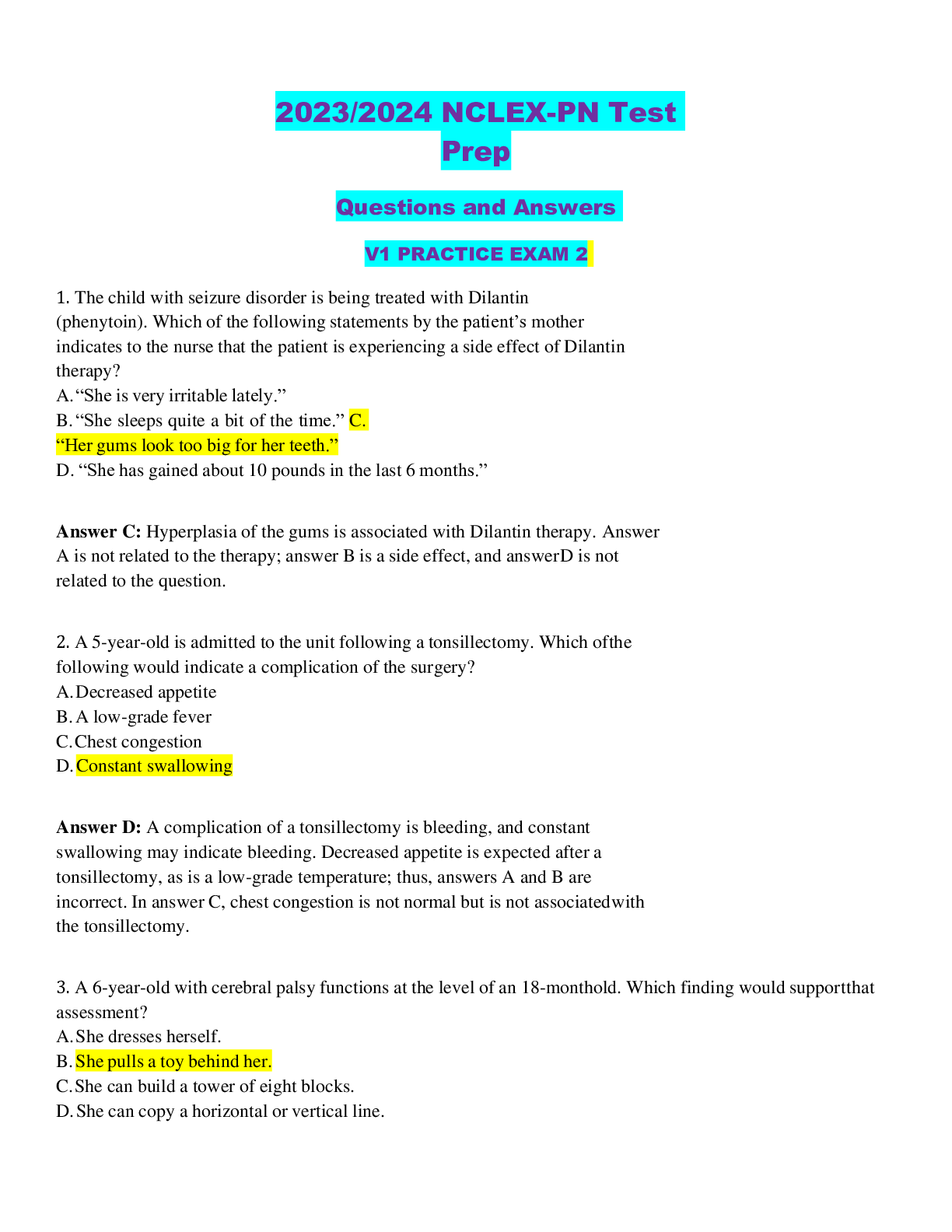

*NURSING > NCLEX-PN > Paediatrics Michael Grant: Notes based on QUB online Med Portal lectures, QUB student manual, NICE G (All)

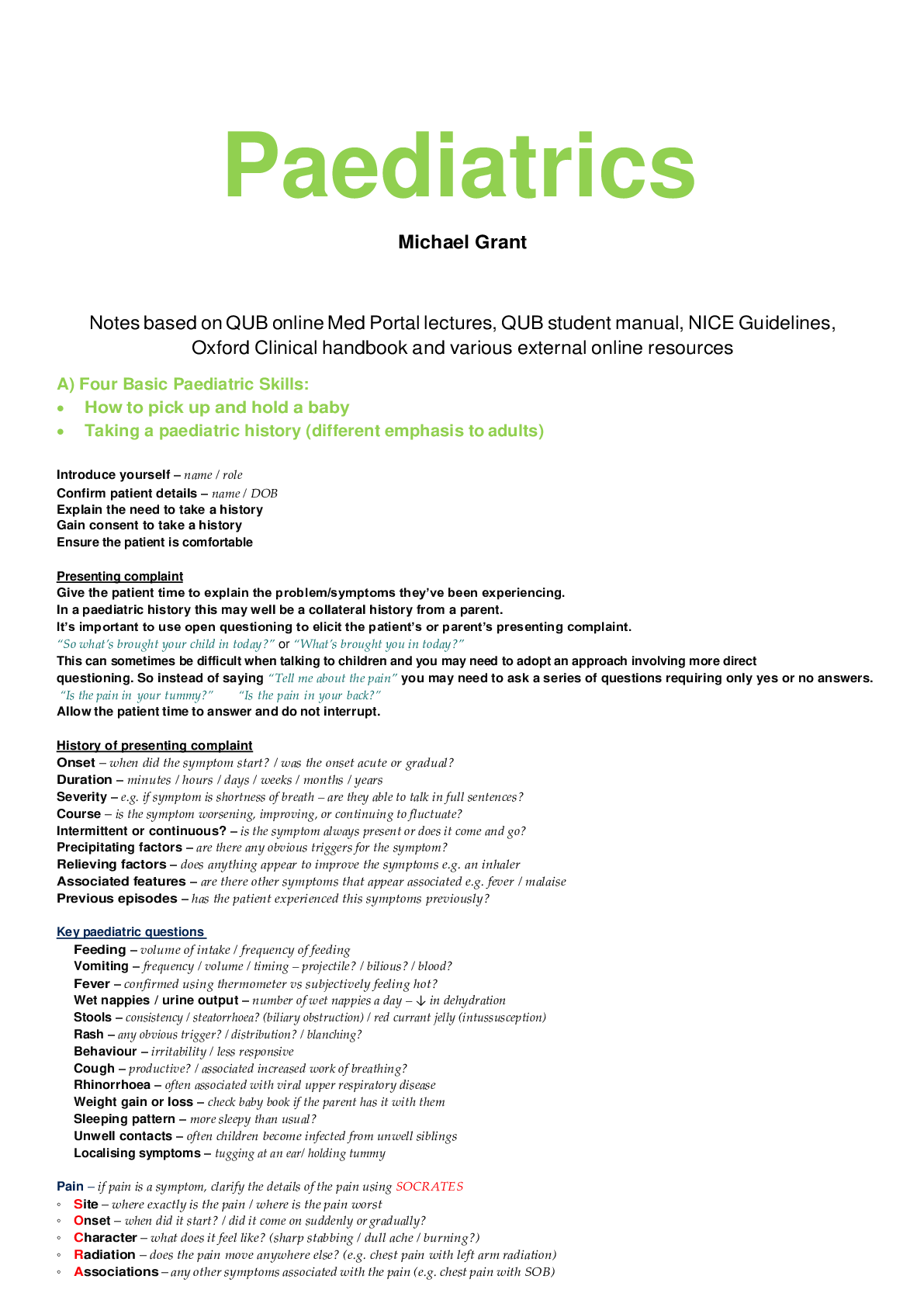

Paediatrics Michael Grant: Notes based on QUB online Med Portal lectures, QUB student manual, NICE Guidelines, Oxford Clinical handbook and various external online resources

Document Content and Description Below