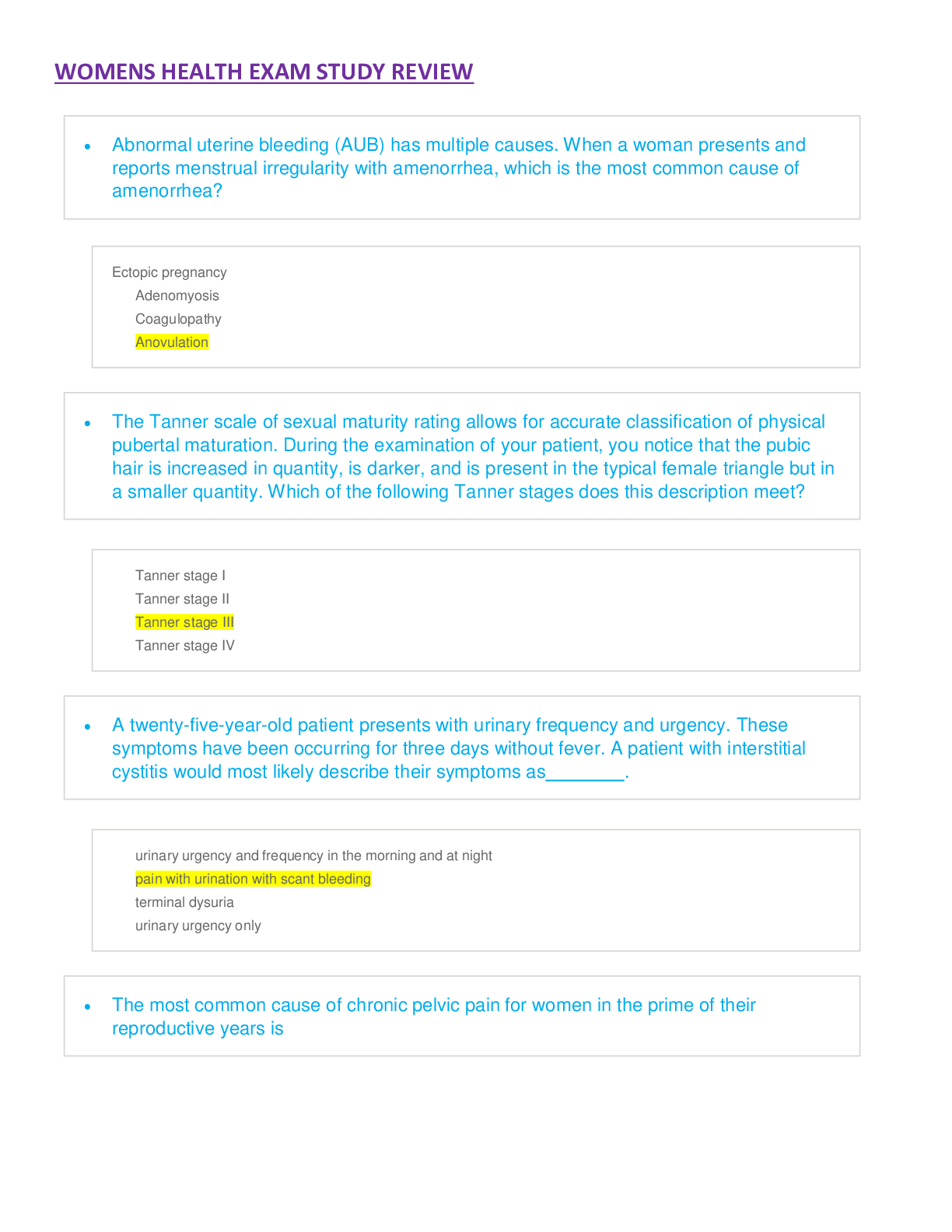

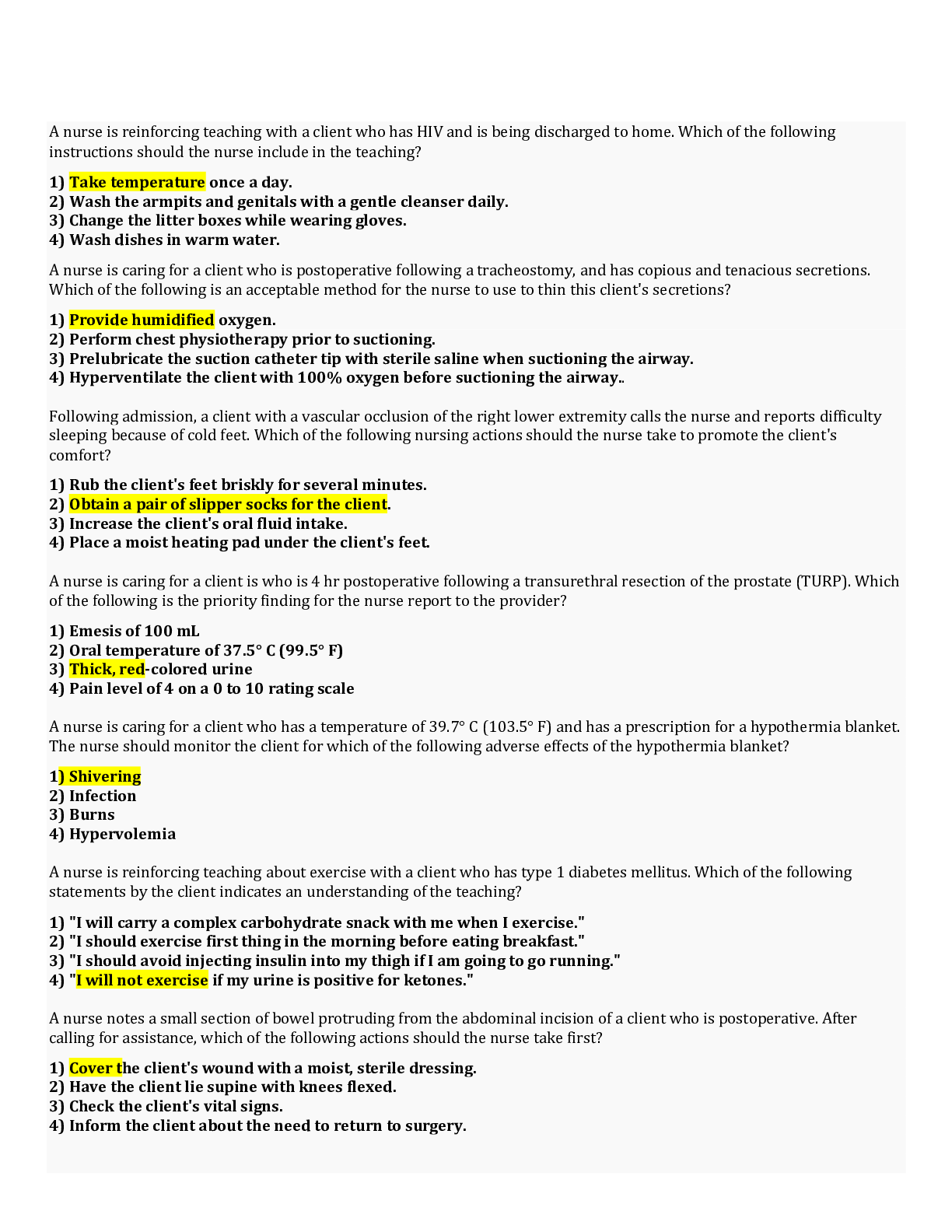

*NURSING > STUDY GUIDE > NSG6006 _ Policies & Practice Standards • State Nurse Practice Act | 5000 (Roles) | AUTHENTIC STUD (All)

NSG6006 _ Policies & Practice Standards • State Nurse Practice Act | 5000 (Roles) | AUTHENTIC STUDY GUIDE | SOUTH UNIVERSITY

Document Content and Description Below