*NURSING > EXAM REVIEW > NR 601 Midterm Exam review November 2019 Week 1 (All)

NR 601 Midterm Exam review November 2019 Week 1

Document Content and Description Below

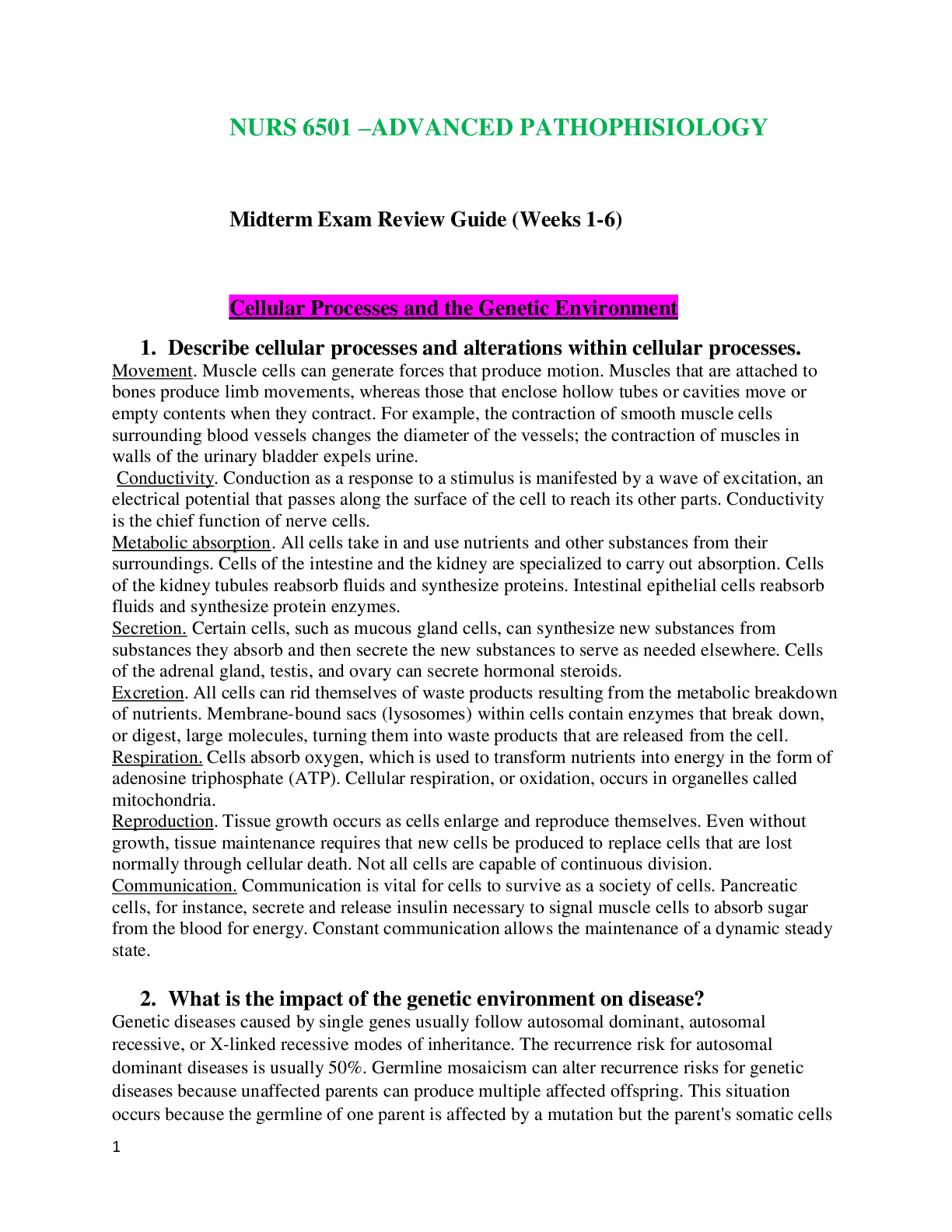

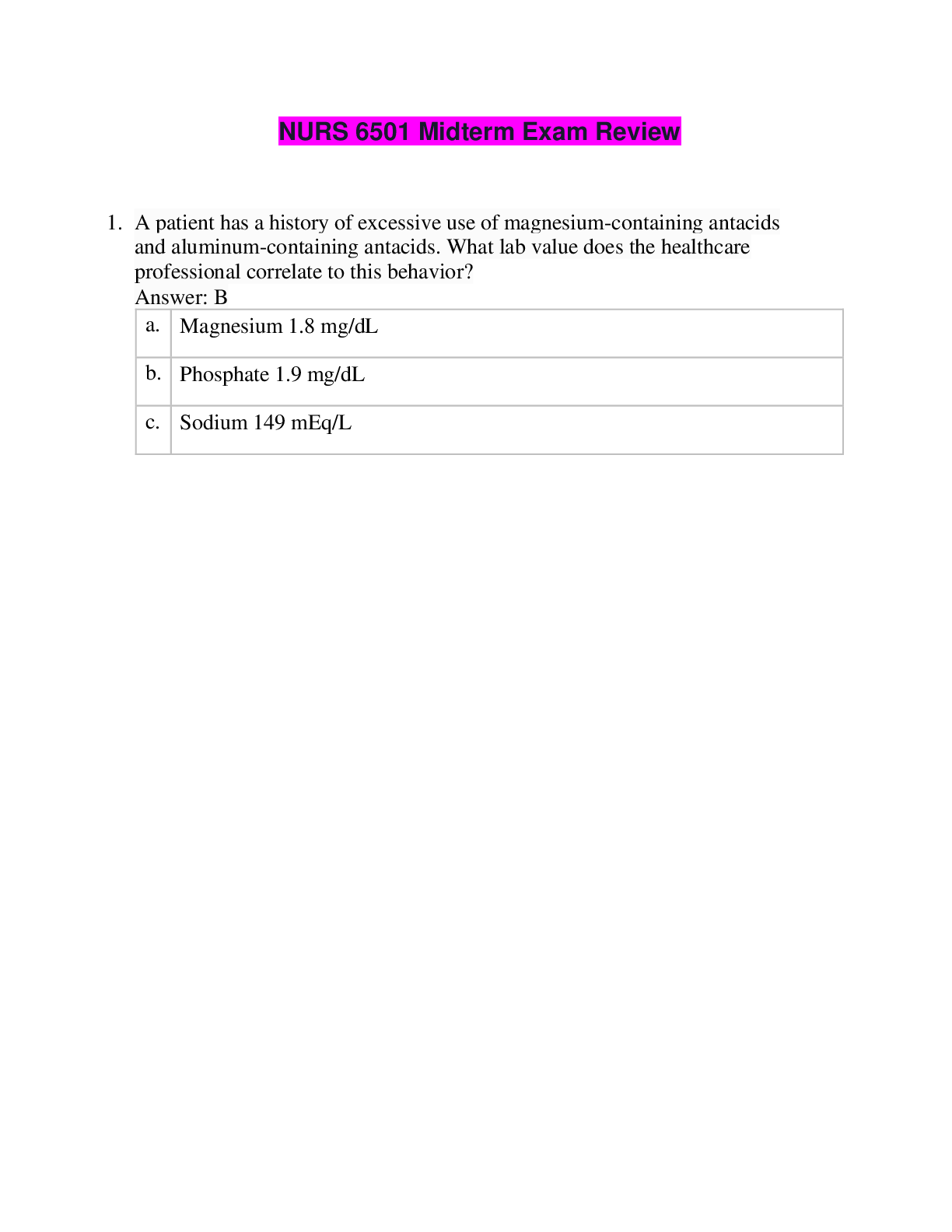

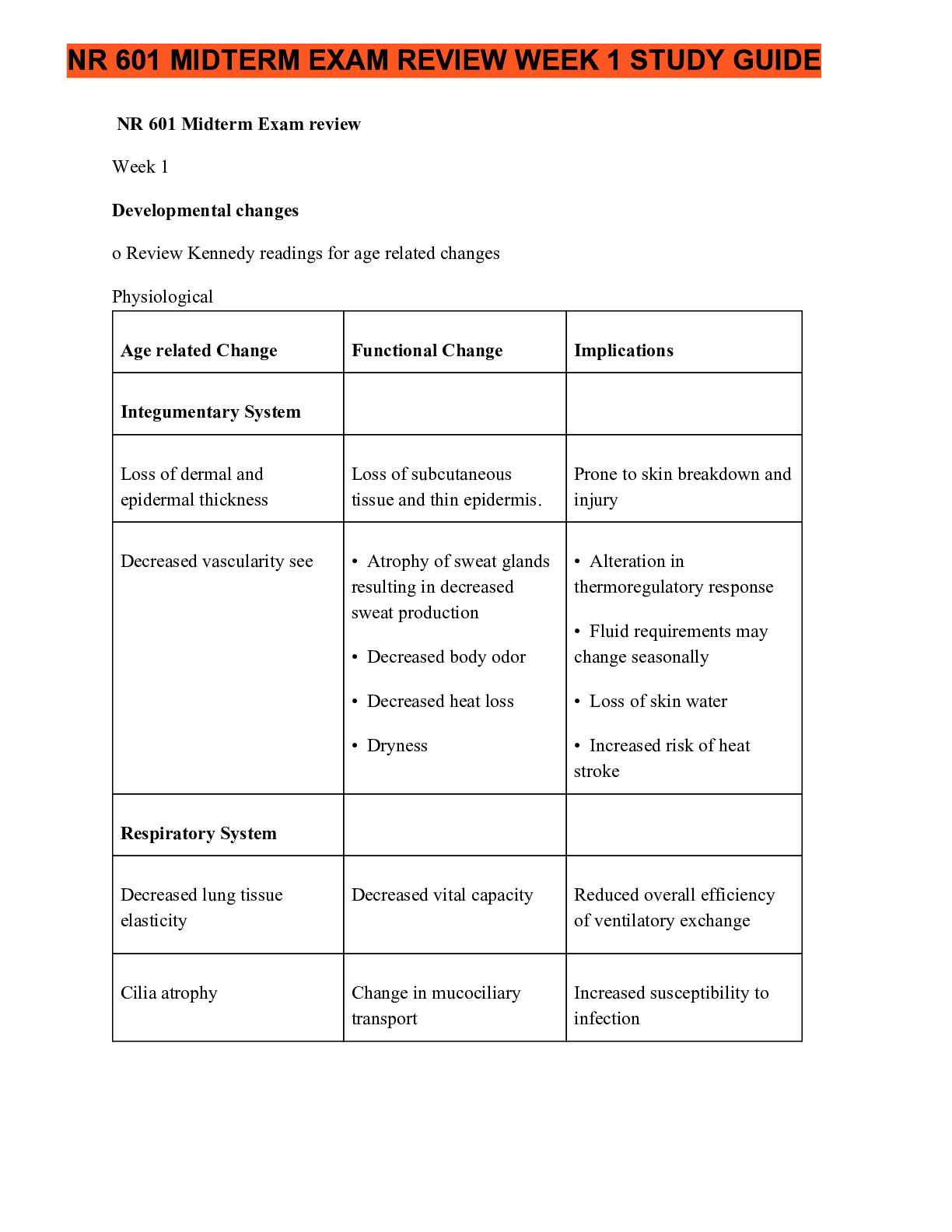

NR 601 Midterm Exam review November 2019 Week 1 Developmental changes o Review Kennedy readings for age related changes Physiological Age related Change Functional Change Integumentary System Loss o... f dermal and epidermal thickness Decreased vascularity see Loss of subcutaneous tissue and thin epidermis. • Atrophy of sweat glands resulting in decreased sweat production • Decreased body odor • Decreased heat loss • Dryness Respiratory System Decreased lung tissue elasticity Cilia atrophy Decreased respiratory muscle strength Decreased vital capacity Reduced overall efficiency of ventilatory exchange Change in mucociliary transport • Reduced ability to handle secretions and reduced effectiveness against noxious foreign particles • Partial inflation of lungs at rest Increased susceptibility to infection Increased risk of atelectasis Prone to skin breakdown and injury • Alteration in thermoregulatory response • Fluid requirements may change seasonally • Loss of skin water • Increased risk of heat stroke ImplicationsCardiovascular System Heart valves thicken and become fibrotic Fibroelastic thickening of the sinoatrial node; decreased number of pacemaker cells Decreased baroreceptor sensitivity (stretch receptors) GI Liver becomes smaller Decreased muscle tone Reduced stroke volume, cardiac output; may be altered Slower heart rate Decreased responsiveness to stress Increased prevalence of arrhythmias Decreased sensitivity to changes in blood pressure Prone to loss of balance, which increases the risk for falls Decreased storage capacity Altered motility Increases risk of constipation, functional bowel syndrome, esophageal spasm, diverticular disease Decreased basal metabolic rate (rate at which fuel is converted into energy) NE CONDE) Lab results Lab Test UA Protein May need fewer calories Normal Changes with age Comments 0-5mg/100ml Rises slightly May be due to kidney changes with age, urinary tract infection, renal pathology Specific Gravity 1.005-1.020 Lower max in elderly 1.016-1.022 Decline in nephrons impairs ability toconcentrate urine Hematology ESR Men: 0-20 Women: 0-30 Iron Binding 50-160mcg/dl 230-410mcg/dl Hemoglobin Men: 13-18g/100ml Women: 12-16g Hematocrit Men: 45-52% Women 37-48% Significant increase Neither sensitive nor specific in aged Slight decrease Decrease Men: 10-17g Women: None noted Slight decreased speculated Leukocytes 4,300–10,800/mm3 Drop to 3,100– 9,000/mm3 Anemia common in the elderly Decline in hematopoiesis Decrease may be due to drugs or sepsis and should not be attributed immediately to age Lymphocytes 00–2,400 T cells/mm3 50–200 B cells/mm3 T-cell and B-cell levels fall Platelet Blood Chemistry Albumin 150,000–350,000/ No change in number Infection risk higher; immunization encouraged 3.5–5.0 Decline Related to decrease in liver size and enzymes; protein-energymalnutrition common Globulin 2.3–3.5 Total serum protein 6.0–8.4 g Slight increase No change Decreases may indicate malnutrition, infection, liver disease Blood urea nitrogen Men: 10–25 Women: 8–20 mg Creatinine 0.6–1.5 mg Creatinine clearance 104–124 mL/min Increases significantly up to 69 mg Increases significantly up to 69 mg Increases to 1.9 mg Related to lean body mass decrease Decreases 10%/decade after age 40 years Glucose tolerance 62–110 mg/dL after fasting; >120 mg/dL after 2 hours postprandial Alkaline phosphatase 13–39 IU/L Slight increase of 10 mg/dL/decade after 30 years of age Increase by 8–10 IU/L Used for prescribing medications for drugs excreted by kidney Diabetes increasingly prevalent; drugs may cause glucose intolerance Elevations >20% usually due to disease; elevations may be found with bone abnormalities, drugs (e.g., narcotics), and eating a fatty meal o Atypical disease presentations 1. Acute abdomenAbsence of symptoms or vague symptoms, acute confusion, mild discomfort and constipation, some tachypnea and possibly vague respiratory symptoms, appendicitis pain may begin in right lower quadrant and become diffuse 2. Depression Anorexia, vague abdominal complaints, new onset of constipation, insomnia hyperactivity, lack of sadness 3. Hyperthyroidism Hyperthyroidism presenting as “apathetic thyrotoxicosis,” i.e., fatigue and weakness; weight loss may result instead of weight gain; patients report palpitations, tachycardia, new onset of atrial fibrillation, and heart failure may occur with undiagnosed hyperthyroidism 4. Hypothyroidism Hypothyroidism often presents with confusion and agitation; new onset of anorexia, weight loss, and arthralgias may occur 5. Malignancy New or worsening back pain secondary to metastases from slow growing breast masses Silent masses of the bowel 6. Myocardial Absence of chest pain infarction (MI), vague symptoms of fatigue, nausea, and a decrease in functional and cognitive status; classic presentations: dyspnea, epigastric discomfort, weakness, vomiting; history of previous cardiac failure, higher prevalence in females versus males Non-Q-wave MI 7. Overall infectious diseases process Absence of fever or low-grade fever, malaise 8. Sepsis Without usual leukocytosis and fever, falls, anorexia, new onset of confusion and/or alteration in change in mental status, decrease in usual functional status 9. Peptic ulcer disease Absence of abdominal pain, dyspepsia, early satiety, painless, bloodless, new onset of confusion, unexplained, tachycardia, and/or hypotension 10. PneumoniaAbsence of fever; mild coughing without copious sputum, especially in dehydrated patients; tachycardia and tachypnea; anorexia and malaise are common; alteration in cognition. 11. Pulmonary edema Lack of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or coughing; insidious onset with changes in function, food or fluid intake, or confusion 12. Tuberculosis (TB) Atypical signs of TB in older adults include hepatosplenomegaly, abnormalities in liver function tests, and anemia 13. Urinary tract infection Absence of fever, worsening mental or functional status, dizziness, anorexia, fatigue, weakness o Geriatric syndromes refers to conditions that involve multiple organ systems. Most common are delirium, falls, dizziness and incontinence. risk factors include: older age, cognitive impairment, functional impairment, and impaired mobility. Bowel incontinence- involuntary passage of stool or the inability to control stool from expulsion. More prevalent in women than men. 3 types: urge incontinence, passive incontinence, and fecal seepage. urge- has desire to go but cannot make it to the toilet despite attempts to avoid defecating. Passive-involuntary loss of gas and stool without awareness. fecal seepage- leakage of stool after a normal bowel movement. etiology : a number of reasons including GI issues, cognitive or neurological diseases. Treatment: treat related etiology such as impaction of increasing fiber. Habit training is also recommended. Once clear evidence of no impaction, infection, or cause is determined. antidiarrheal medication like Imodium can be tried. For retrosphincter dysfunction biofeedback with strengthening exercises for the sphincter can be done. Constipation: presence of 2 or more symptoms: decreased stool frequency, straining, hard stools, sensation of incomplete emptying, blockage at anorectal site. constipation is most common digestive complaint.Cough: forceful expelling of air from the lungs involving the use of accessory muscles of the chest and constriction of the glottis. dehydration: caused by too little fluid intake, too much fluid lost or both. Chronic diseases like diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and renal diseases make elderly sensitive to fluid shifts. Diarrhea: Passage of increased stool frequency, liquidity, or volume. Most episodes are caused by viral gastroenteritis. Chronic diarrhea is defined as lasting longer than 4 weeks. Dizziness: common clinical categories include vertigo, light-headedness, unsteadiness, or gait instability, and disequilibrium. Falls: WHO defines this as an event that results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground, floor, or other lower level. can be witnessed or unwitnessed. due to intrinsic factors or extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include age, weakness, gait/balance, poor vision and postural hypotension. Extrinsic factors involve environment conditions like lack of handrails, poor lighting, obstacles, slippery surfaces, certain medication, and polypharmacy. Fatigue ● Description ○ Subjective state often described as a feeling of tiredness, weariness, lack of energy, or exhaustion that is unrelieved or only partially relieved by rest ○ Often results in an inability to initiate normal activity; a reduced capacity to maintain activity; and difficulty with concentration, memory, and emotional stability ○ Chronic fatigue syndrome occurs when fatigue lasts longer than 6 months and is not relieved with rest ○ Fatigue could also be a symptom of another illness and any older person with this complaint should obtain a medical evaluation and work-up. ● Etiology ○ Occurs normally with inadequate rest, excess exertion, or insufficient diet ○ Fatigue in older adults may be an early indicator of the aging process, as well as debility or another disorder ● Occurrence ○ 25% of the US population ● Age ○ Common among the elderly ● Gender ○ More common in women ● Ethnicity ○ Not significant ● Contributing Factors ○ Poor dietary habits, overexertion, alcohol abuse, smoking, stress, chronic illness, drug interactions, misuse of drugs, and sleep apnea ○ In the older adult individual, it is compounded by a decrease in muscle strength, loss of muscle neurons, muscle atrophy, a decrease in hormone levels, and lack of exercise. ● Signs and symptoms○ Conduct a complete symptom assessment, including the onset; duration; severity; and precipitating, aggravating, and relieving factors. ○ Identify other indicators or associated symptoms of fatigue, which may include decreased energy expenditure, decreased endurance, sleep disturbance, attention deficits, somatic complaints (aching body, tired eyes), dyspnea, and weakness ○ Carefully review the adequacy of the diet, all medications (evaluating for potential medication side effects), activity level (including degree of independence of ADLs), and potential causes or contributing factors. Identify the impact fatigue is having on the person’s ADLs and quality of life and current stressors. ○ Distinguish between generalized fatigue and actual weakness by testing for muscle strength and presence of localized tenderness ○ A thorough physical examination will include a mental status examination to screen for dementia and rule out depression. ● Diagnostic tests ○ Diagnostic tests on all patients with persistent unresolved fatigue should include CMP, CBC with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and/or C-reactive protein, because these are low cost and offer significant screening capacity. ○ Thyroid function, urinalysis, and pulmonary function tests. ○ If symptoms and signs indicate cardiac decompensation, a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) may indicate degree of heart failure and an EKG may reveal cardiac arrhythmias, enlargement of the heart, myocardial infarction, or abnormalities in the conduction system ● Differential diagnosis ○ Psychiatric disorders, including depression and generalized anxiety disorder, account for 70% of cases of fatigue ○ Fatigue that cannot be relieved by rest or sleep is often a sign of disease. ● Treatment ○ Symptom management includes regular exercise, attention-restoring activities, psychosocial techniques, energy conservation measures, good sleep hygiene, improving diet, and possibly adding nutritional supplements ○ Psychostimulants may be considered for opioid-related somnolence, cognitive impairment, and depression ● Follow up ○ Monitor the patient periodically as indicated by diagnosis or symptoms, symptom persistence, and disability associated with the symptom ● Sequelae ○ The potential for complications relates to the cause of fatigue and the impact the symptom has on the person’s function ● Prevention/Prophylaxis ○ Optimal health maintenance, including maintaining a healthy diet, regular exercise, and good sleep hygiene, may prevent or enable early recognition of signs and symptoms of systemic or psychological illness ● Referral ○ May be indicated based on the results of the work-up ● Education ○ If the fatigue has a physiological cause, teaching should be related to the findings; psychological counseling, changes in the environment, behavior modification, and stress reduction may be needed Goal of fatigue management - provide the patient with self-help tools to eliminate or alleviate fatigueHeadache: Hematuria: Description: Presence of RBCs in the urine, classified either gross or microscopic Gross hematuria: urine appears either red or brown in color to the naked eye Microscopic hematuria: identified by lab analysis. Significant if 3 or more RBCs per high- power field on accurately collected urine specimen. *requires evaluation, 5% with microscopic hematuria are found to have malignancy, & 30- 40% with gross hematuria are found to have malignancy Etiology: renal or contamination from outside the urinary tract. Renal hematuria may result from glomerular or nonglomerular causes.Source of hematuria may be the upper collection system (renal, ureter) and/or lower collection system (bladder, prostate, urethra). Common finding on routine UA and etiologies range from life-threatening to benign incidentals. Patho depends on the anatomical site from which blood loss occurred, older adults, most common causes are malignancy or BPH Occurrence: prevalence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria ranges from 2% to 31% in the adult population, older than 50 yrs., prevalence 13% Age: increases with age, younger pts are less likely to have an etiology identified Ethnicity: not significant Contributing factors: infection, anticoagulation, renal calculi, trauma, anatomical defects such as rectocele, menstruation, atrophic vaginitis, renal disease, or recent urological procedure, malignancy include age more than 35 yrs. male sex, current or past history of smoking, occupational exposures to chemicals or dyes, hx of gross hematuria, chronic cystitis,pelvic irradiation, exposures to cytotoxic agents S/Sxs: thorough HX, presence of visible blood in the urine, Hx of vigorous exercise, recent prostate examination or procedure, recent trauma to the abdomen, recent catheterization, menstruation, renal disease, viral illness, medications (analgesics, antibiotics, anticoagulants, NSAIDS). Symptoms represents kidney disease or stone. urinary frequency, lower abdominal pain or dysuria, which may indicate UTI. PE: focus on abdominal/flank pain, urogenital examination, prostate, testicular and vaginal examination Dx Tests: UA with microscopy. Urine dipstick evaluation may be misleading because it lacks the ability to distinguish RBCs from myoglobin or HgB, should confirm with heme-positive dipstick with a microscopic UA. CMP for metabolic abnormalities, elevated creatinine: indicates acute or chronic renal disease and should be referred to nephrologist. PT/INR if on anticoagulation and CBC. Multiphasic CT urography or IV pyelogram if suspicious of kidney stone, renal mass or malignancy. Cystoscopy for patients 35 years of age, pts younger than 35 yrs if no other reason for hematuria is present, pts of any age if with risks factors for CA., dx bladder or prostatic CADDX: infection or supratherapeutic anticoagulation should be r/o as reversible causes of hematuria. serious causes: glomerular disease, renal calculi, trauma, anatomical defects, or malignancy TX; directed at the cause, asymptomatic (isolated) does not require treatment. Appropriate ABT therapy for UTI should resolve the hematuria, anticoagulation is the cause, adjustment may resolve the problem, kidney stone, initial tx may be pain management and oral hydration. Urosepsis, AKI, anuria, unrelenting N/V should be referred immediately FF-up: repeat UA should be obtained 6 weeks after initial tx for any infection, vigorous exercise, or trauma to make sure that the hematuria has cleared. Refer to urology for gross or microscopic hematuria. Persistent hematuria w/ initial (-) urological work-up, a repeat UA should be done yearly and a full repeat evaluation very 3-5 yrs for ongoing hematuria. Referral to nephro if hematuria persists with renal impairment Sequelae: fairly common in young adults under 35 yrs. It could be a sign of malignancy, should not be ignored, even if it is transient. May indicate renal disease, when proteinuria is present, referral to nephro for 2nd opinion. Prevention/Prophylaxis: USPSTF does not endorse routine screening for asymptomatic hematuria due to lack of evidence Referral : Primary care providers can initiate testing to verify presence of hematuria and treat hematuria if Dx is clear. Referral to nephro is indicated for the presence of proteinuria, RBC casts, dysmorphic RBCs, or elevated serum creatinine level. Referral to urology: hematuria persisting after treatment for a UTI, taking anticoagulants, or in the absence of benign cause, gross and microscopic hematuria Education: Counsel family and patients to seek medical advice about gross hematuria, plus s/sxs to report such as urinary frequency, dysuria, flank and abdominal pain. Educate pts and families abt the SEs of OTC drugs and RX meds, effects of anticoagulant therapy and to call immediately if the pt. notices any hematuria because this may mean the pt’s drug level is too high. Involuntary weight loss: Joint pain: priutis: Tremor: is the most common form of involuntary movement and is characterized by rhythmic oscillation of a body part that can be classified according to the circumstances under which it occurs. Etiology: Because of the vast number of causes of tremor, etiological classification is not helpful. Terms used to describe the clinical phenomenology of tremor include rest tremors and action tremors.Rest tremor occurs when muscle is not activated voluntarily, and the relevant body part is fully supported against gravity Action tremor is present with voluntary contraction of muscle. Action tremors can be sub-classified further into postural, kinetic, and isometric tremor. Postural tremor is present while voluntarily maintaining a position against gravity. Kinetic tremor may occur during any form of voluntary movement of the affected body part. Isometric tremor occurs with muscle contraction against a rigid stationary object. The most common tremor is enhanced physiological tremor followed by essential tremor and then parkinsonian tremor. Occurrence: Tremor is the most common movement disorder encountered in clinical practice. Everyone has a low-amplitude physiological tremor that can be observed when the arms are extended. Enhanced physiological tremor is a physiological tremor that comes and goes with anxiety, caffeine, and fatigue. In 50% of cases, the disease is familial (autosomal dominant, meaning 50% of an affected individual’s children have it). More than 70% of patients with Parkinson’s disease have tremor as the presenting symptom. Less common are cerebellar tremor, psychogenic tremor, dystonic tremor, and tremor associated with Wilson’s disease. Age: Most studies report a significant age-associated increase in the prevalence of essential tremor. Essential tremor begins in young to middle-aged people and gradually intensifies with age. Tremors in older adults are more likely to be of the essential or parkinsonian type. Gender: Tremor afflicts both genders equally, with perhaps slightly more frequency in men than in women. Ethnicity: Tremor is more prevalent in Caucasians than in African Americans, and is of intermediate prevalence in Hispanics. Contributing Factors: During times of stress, the amplitude of a physiological tremor increases. Fatigue, anxiety, hyperthyroidism, systemic illness, use of medications, drug withdrawal (especially from alcohol), use of methylxanthines, and excess caffeine intake can exaggerate tremor. Medications that can cause or exacerbate tremor include those that stimulate the sympathetic nervous system and psychoactive medications. Signs and Symptoms: The first step in the evaluation of tremor is to categorize the tremor based on activation conditions, distribution, and frequency. Determine the duration and age of onset of symptoms, exacerbating or alleviating factors, and any family history of tremor or other neurological disorders. Include any associated symptoms, such as bradykinesia or rigidity (suggesting Parkinson’s disease) or ataxia and nystagmus (suggesting cerebellar disease). The patient’s medication history, any exposure to toxins, and the presence of illness should be noted. History is important, but the diagnosis is based on clinical physical examination findings. Tremor may occur in various body parts, such as the hands, head, facial structures (chin, tongue, lips, and ears), vocal cords, trunk, and legs. Of all tremors, 94% occur in the hands, either unilaterally or bilaterally. On physical examination, it is important to conduct a thorough tremor-focused neurological examination: muscle tone is checked throughout the body, cranial structures (including the mouthand jaw) are examined at rest and in action, and the tongue is observed during rest and protrusion. To distinguish properly between resting and action tremors, patients should be evaluated while supine and when seated with the arms fully supported. The upper extremities are examined in an outstretched position with the hands supine (palms up), sideways (semi-prone), and then prone (palms down). The semi-prone position enhances essential tremor, whereas the supine position inhibits it. In the wing position (i.e., with apposition of the index fingers close to each other but not touching), proximal tremor may be identified. Goal- directed activities are performed, such as finger-to-nose, heel-to-shin, and toe-to-finger movements. The patient is asked to recite a standard paragraph and enunciate a sustained vowel. Handwriting samples are obtained (e.g., script, numbers, Archimedes spirals). Gait is evaluated for shuffling and unsteadiness, and Romberg (station) and balance testing are conducted. Careful evaluation is performed for signs associated with tremor syndromes. Bradykinesia and postural abnormalities are evaluated by observing difficulty rising from a seated position, decreased arm swing, and masked facies. Patients with essential tremor typically have handwriting that is shaky and large, whereas the handwriting of patients with Parkinson’s disease initially may be of normal size and progressively become smaller (micrographia). Archimedes spirals drawn by essential tremor patients tend to illustrate natural fluctuations in tremor magnitude. Diagnostic Tests: No specific tests are routinely ordered for tremors. Electromyography is used to subdivide tremors according to their rate and their relationship to posture of limbs and volitional movement. Tremor frequency usually is categorized as low frequency (less than 4 Hz), medium frequency (4 to 6 Hz), and high frequency (greater than 6 Hz). The diagnosis of tremor is primarily clinical; however, laboratory testing may be necessary to exclude certain conditions that may be associated with tremor, such as metabolic disturbances, including hyperthyroidism (e.g., through thyroid function tests) and Wilson’s disease. Brain imaging may be indicated for select patients, particularly patients with tremor that is unilateral, of sudden onset, or associated with atypical clinical features. For difficult cases, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) to visualize the integrity of dopaminergic pathways may be useful in diagnosing Parkinson’s disease. Differential Diagnosis: The differential diagnosis, in general practice, is almost always between Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor. Physiological Tremor: A normal phenomenon, physiological tremor occurs in all contracting muscle groups. Although seldom visible to the naked eye, physiological tremor often may be detected when the fingers are firmly outstretched with a piece of paper placed over the hands. Enhanced Physiological Tremor (or an Intensification of Physiological Tremor to Detectable Levels): Physiological tremor may be enhanced under conditions of stress, anxiety, fatigue, exercise, cold, hunger, stimulant use, alcohol withdrawal, or metabolic disturbances such as hypoglycemia or hyperthyroidism. Although the tremor is typically low in amplitude and high in frequency (8 to 12 Hz), it may be clinically indistinguishable from essential tremor. Essential Tremor (4 to 12 Hz): Essential tremor is a persistent postural and kinetic tremor that predominantly affects the hands and forearms. Classically, to show the tremor, the patient is asked to extend the arms in front of the body. The legs are affected less often. Although less frequently involved, the presence of tremor in the head and/or voice is a strong indication of essential tremor and is especially useful in differentiating the syndrome from Parkinson’s disease. Head tremor, which is also postural, disappears when the head is supported. Listening to the patient speak orhaving the patient hold a musical note as long as possible may reveal a quivering intonation. A resting component is present only rarely and typically occurs in the most advanced cases. Parkinsonian Tremor Syndromes (4 to 6 Hz): Parkinsonian tremor syndromes involve resting tremor that is often asymmetrical. Tremor may be observed when muscles are relaxed, such as when the hands are resting on the lap, and may affect hands, feet, mandible, and lips. Tremor disappears during sleep. Typical is an alternating tremor of the thumb against the index finger— pill-rolling tremor. Although rest tremor is a diagnostic criterion for Parkinson’s disease, other forms of tremor also may be present. Treatment: Tremor should be treated if it causes disability. First-line treatment for tremor is oral medication. Beta blockers, anticholinergic medication, and levodopa are useful modalities for resting tremor. Kinetic tremor may respond to beta blockers, primidone, anticholinergics, and alcohol. When there is a lack of response to medical treatment or when tremor results in severe disability, a patient may be considered for neurosurgery. Specific treatments for the most common causes are noted next. Physiological Tremor: Usually no treatment is required for physiological tremor. When exaggerated, however, it may interfere with activities requiring extreme precision. Identify and remove precipitating causes and contributing causes. If the precipitating cause cannot be removed, propranolol may be effective. Essential Tremor: Varying degrees of control in essential tremor have been obtained with the beta blocker propranolol and the anticonvulsant agent primidone. Either agent may be considered an appropriate first-line therapy for the symptomatic management of essential tremor. When appropriate, these agents may be administered in combination with benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam. If the medication is of no benefit at a dose that causes adverse effects, dose levels should be tapered down gradually and eventually discontinued. If a medication is documented to be beneficial, it may be continued at the regulated doses, and the next medication may be added to the drug regimen. If the response to a drug is adequate and the dose is well tolerated, you may continue to monitor tolerance and possibly increase the dose. Physical and psychological measures may be helpful in managing mild tremor. Physical measures may include the application of weights to affected limbs to decrease tremor amplitude. Some patients have experienced benefits with biofeedback, relaxation methods, and other behavioral techniques through alleviation of anxiety or stress that may exacerbate tremor. Alcohol consumption may lead to transient improvement for many with essential tremor. The potential risk of alcohol dependence and abuse among essential tremor patients who drink alcohol to control symptoms is controversial. Alcohol has no impact on the tremor of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonian Tremor: The tremor of Parkinson’s disease results from a loss of striatal dopamine, and this is the rationale for treatment with either the dopamine precursor levodopa or dopamine receptor agonists. Dopaminergic and anticholinergic agents are equally effective, but dopaminergic substances additionally improve other parkinsonian signs, and the potential side effects of anticholinergic medications make these drugs undesirable in the older adult. The combination of levodopa and carbidopa reduces levodopa-induced nausea; a typical starting dose is one tablet of Sinemet 25/100 three times daily. Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (brand name Duopa) is a combination of levodopa and carbidopa that is dosed for 16 hours during wakefulness. It is administered via PEG-J tube supplied by an external box. This route of dosingdecreases tremor by reducing plasma fluctuations that patients on oral levodopa and carbidopa might experience. Patients with severe tremors that are resistant to pharmacotherapy may benefit from ablative surgery and/or deep brain stimulation. For those essential tremor patients who fail medication treatment, transcranial magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy (product name ExAblate Neuro) has been shown to be successful in the treatment of essential tremor. This procedure is noninvasive. Follow-Up: Patients should be evaluated for therapeutic effects and side effects within 1 week of starting treatment. Annual monitoring for weight loss, depression, and decline in functional status is necessary. Sequelae: Functional disabilities may occur in ADLs, including compromised eating, drinking, and preparing food. Decreased caloric intake and weight loss may be observed. Ambulation, especially on stairs, may be hazardous. Withdrawal from social situations may occur, and depression is common. Prevention/Prophylaxis: Reduce factors that can exacerbate the tremor. Continue medication regimen. Referral: A neurologist should be consulted for cerebellar tremors, mixed tremors, or Parkinsonian tremor, or when a focal neurological deficit is identified. An ophthalmologist should be consulted when Wilson’s disease is suspected. A mental health provider or psychiatrist should be consulted when a hysterical tremor is suspected. Physical therapy or occupational therapy may be helpful in advanced or disabling cases. Education: Some patients, particularly patients with severe, disabling tremor, may limit their contacts. Patients must be encouraged to learn as much as they can about their disease to help them cope better with the condition’s progression. When a diagnosis has been established, the natural history of the condition should be explained to patients. It also may be appropriate to recommend counseling. Use of appropriate coping strategies may reduce stress substantially, preventing possible augmentation of tremor owing to anxiety. Referral to appropriate patient support organizations is helpful for most patients. CLINICAL RECOMMENDATION EVIDENCE RATING The diagnosis of tremor is based on clinical information from the history and physical examination. C REFERENCES Deuschl et al., 1998 Sharma & Pandey, 2016 Propranolol and primidone are first-line treatments for essential tremor. A Sharma & Pandey, 2016Tremor amplitude worsens over time if not treated. C Sharma & Pandey, 2016 Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel improves resting tremors. Transcranial magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy successfully treats essential tremor. B Fernandez et al., 2016 B U.S. FDA, 2016 Urinary incontinence: (I realize this is copied and pasted from the book; that’s bc it is late. I will read it and cut it down tomorrow; thanks! However, if anyone is awake and reading this, please feel free to trim away unnecessary excess information.) (UI) is an involuntary loss of urine. Acute UI is generally a result of illness or the effects of medications and is self-limiting when the cause is determined and addressed. Chronic UI has different forms, including stress incontinence, urge incontinence, overflow incontinence, and functional incontinence. Many older women manifest a combination of urge and stress symptoms resulting in mixed incontinence. Etiology: Anatomical changes, factors related to the individual’s medical history, lifestyle, and acute and chronic illnesses, in addition to medications, can result in incontinence that can be either reversible or a permanent condition. Cognitive as well as chronic mental illness, depression, and functional barriers to continence can also affect an individual’s ability to maintain urinary continence. [Show More]

Last updated: 1 year ago

Preview 1 out of 57 pages

Instant download

Instant download

Reviews( 0 )

Document information

Connected school, study & course

About the document

Uploaded On

Sep 08, 2021

Number of pages

57

Written in

Additional information

This document has been written for:

Uploaded

Sep 08, 2021

Downloads

0

Views

44