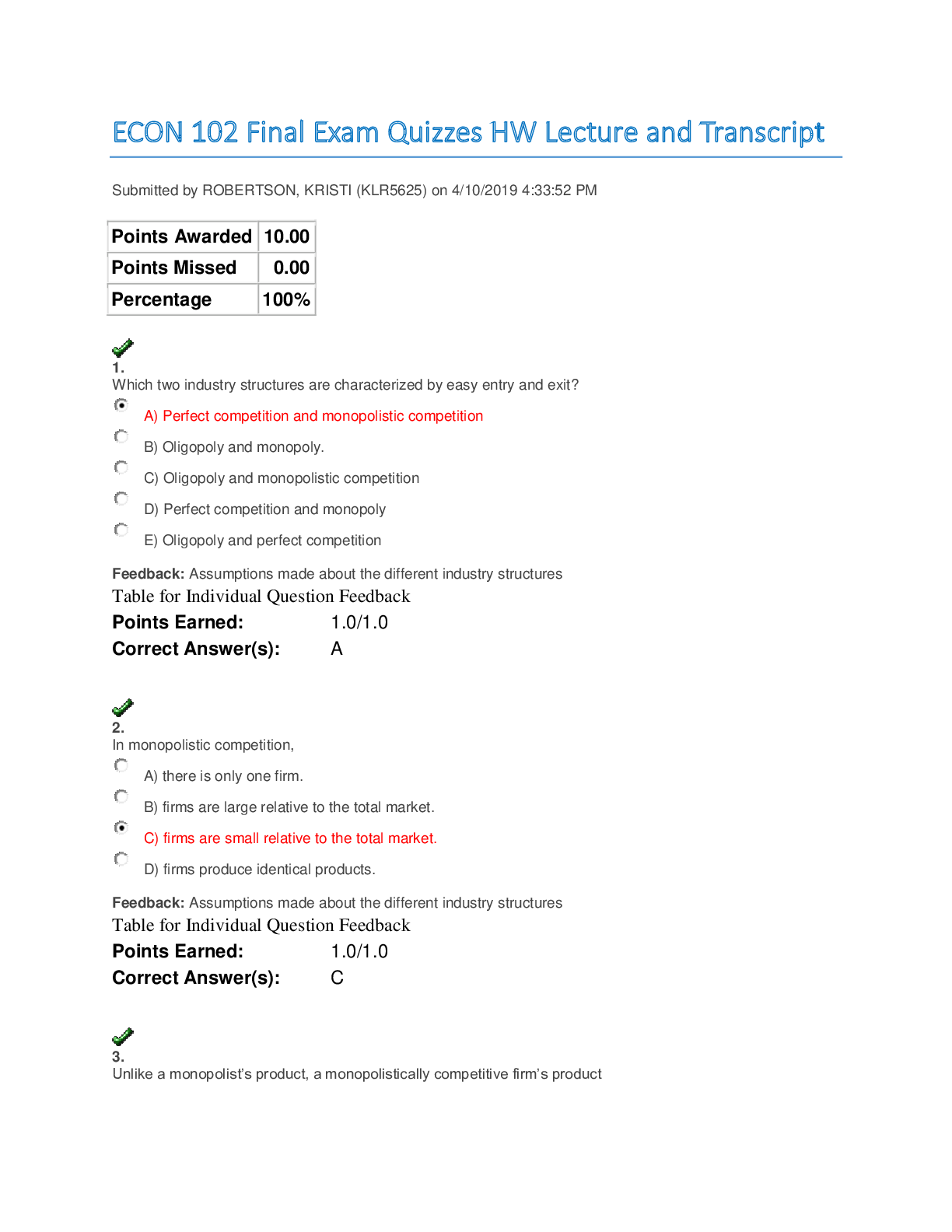

Economics > Dissertation > ECON 102 Final Exam Quizzes HW Lecture and Transcript. (All)

ECON 102 Final Exam Quizzes HW Lecture and Transcript.

Document Content and Description Below